Many components (of libraries like React, Vue, Angular) use the functionality of utility libraries.

Let's consider a React component that displays the number of words in the provided text:

import words from 'lodash.words';function CountWords({ text }: { text: string }): JSX.Element { const count = words(text).length; return ( <div className="words-count">{count}</div> );}

The component CountWords uses the library lodash.words to count the number of words in the string text.

CountWords component has a dependency on lodash.words library.

The components using dependencies benefit from the code reuse: you simply import the necessary library and use it.

However, your component might need diverse dependency implementations for various environments (client-side, server-side, testing environment). In such a case importing directly a dependency is a risk.

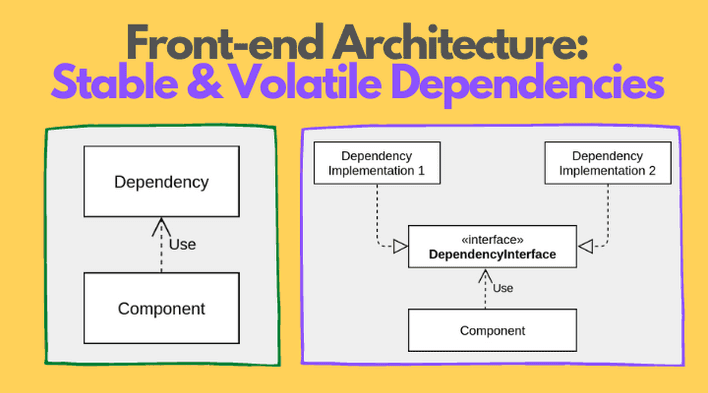

Designing correctly the dependencies is an important skill to architect Front-end applications. The first step to creating a good design is to identify the stable and volatile dependencies and treat them accordingly. In this post, you're going to find out how.

Table of Contents

1. Stable dependencies

Let's recall the example component CountWords from the introduction:

import words from 'lodash.words';function CountWords({ text }: { text: string }): JSX.Element { const count = words(text).length; return ( <div className="words-count">{count}</div> );}

The component CountWords is going to use the same library lodash.words no matter the environment: be it on client-side, be it running on the server-side (if you implement Server-Side Rendering), or even when running unit tests.

At the same time, lodash.words is a simple utility function:

const arrayOfWords = words(string);

The signature of words function won't change much in the future.

Because the dependent component always uses one dependency implementation, and the dependency won't change in the future — such dependency is considered stable.

Examples of stable dependencies are the utility libraries like lodash, ramda.

Moreover, the JavaScript language itself provides:

- Utility functions, like

Object.keys(),Array.from() - Methods on primitives and objects, like

string.slice(),array.includes(),object.toString()

All the built-in functions that the language provides are also considered stable dependencies. You can use them safely and depend directly upon them.

However, aside from stable ones, some dependencies may change under certain circumstances. Such volatile dependencies have to be segregated from stable ones and designed differently.

Let's see what volatile dependencies are in the next section.

2. Volatile dependencies

Consider a Front-end application that supports also Server-Side Rendering. Your task is to implement a user login page.

A login form is displayed when the user first loads the login page. If the user introduces the correct username and password in the login form and hits submit, then you create a cookie loggedIn with value 1.

As long as the user is logged in (the cookie loggedIn is set and has value 1) display a message 'You are logged in'. Otherwise, just display the login form.

Having the app requirements setup, let's discuss potential ways of implementation.

To determine whether loggedIn cookie is set-up, you have to consider the environment where the application runs. On the client-side, you can access the cookie from document.cookie property, while on the server-side you'd need to read the HTTP request header cookie.

The cookie management is a volatile dependency because the component chooses the concrete implementation by environment: client-side or server-side.

Generally, the dependency is volatile if any of the following criteria are met:

- The dependency requires runtime environment setup for the application (network access, web services, file system)

- The dependency is in development

- The dependency has non-deterministic behavior (random number generator, access of current date, etc).

An example of volatile dependency is, as mentioned, the cookie management library which has different implementations on client and server-side. Another example of volatile dependency is the library to access a database or a fetching library that accesses the network.

Even a dependency that is still in development or one you can probably change for an alternative solution in the future can also be volatile.

A good rule of thumb to distinguish a volatile dependency is to analyze how easy you can unit test the component that depends on it. If the dependency requires a lot of setup ceremony and mocks to be tested (e.g. a fetching library requires mocking network requests), then most likely it's a volatile.

2.1 A bad design

Your component should not directly import volatile dependencies.

But let's deliberately make this mistake:

import { cookieClient } from './libs/cookie-client';import { cookieServer } from './libs/cookie-server';import LoginForm from 'Components/LoginForm';export function Page(): JSX.Element { const cookieManagement = typeof window === 'undefined' ? cookieServer : cookieClient; if (cookieManagement.get('loggedIn') === '1') { return <div>You are logged in</div>; } else { return <LoginForm /> }}

Page component depends directly on both cookieClient and cookieServer libraries. The component selects the necessary implementation by checking whether the window global variable is available (meaning the app runs in a browser) or not (meaning the app runs on server).

Why implementing the cookie management volatile dependency such way is a problem? Let's see:

- Tight coupling to all dependency implementations. The component

Pagedepends directly oncookieClientandcookieServerimplementations - Dependency on the environment. Every time you need the cookie management library, you have to invoke the expression

typeof window === 'undefined'to determine whether the app runs on the client or server-side, and choose according to cookie management implementation. - Unnecessary code. The client-side bundle is going to include the

cookieServerlibrary which isn't used on the client-side. And vice-versa for server-side. - Difficult testing. The unit tests of

Pagecomponent would require lots of mockups like settingwindowvariable and mockupdocument.cookie

Is there a better design? Let's find out!

2.2 A better design

Making a better design to handle volatile dependencies requires a bit more work, but the outcome worth it.

The idea consists in applying the Dependency Inversion Principle and decouple Page component from cookieClient and cookieServer. Instead, let's make the Page component depend on an abstract interface Cookie.

First, let's define an interface Cookie that describes what methods a cookie library should implement:

// Cookie.tsexport interface Cookie { get(name: string): string | null; set(name: string, value: string): void;}

Now let's define the React context that's going to hold a specific implementation of the cookie management library:

// CookieContext.tsximport { createContext } from 'react';import { Cookie } from './Cookie';export const CookieContext = createContext<Cookie>(null);

CookieContext injects the dependency into the Page component:

// Page.tsximport { useContext } from 'react';import { Cookie } from './Cookie';import { CookieContext } from './CookieContext';import { LoginForm } from './LoginForm';export function Page(): JSX.Element { const cookie: Cookie = useContext(cookieContext); if (cookie.get('loggedIn') === '1') { return <div>You are logged in</div>; } else { return <LoginForm /> }}

The only thing that Page component knows about is the Cookie interface, and nothing more. The component is decoupled from the implementation details of how cookies are accessed.

Page component doesn't care about what concrete implementation it gets. The only requirement is that the injected dependency to conform to the Cookie interface.

The necessary implementation of the cookie management library is setup by the bootstrap scripts on both client and server sides.

Here's how you would compose the cookie management dependency on client-side:

// index.client.tsximport ReactDOM from 'react-dom';import { Page } from './Page';import { CookieContext } from './CookieContext';import { cookieClient } from './libs/cookie-client';ReactDOM.hydrate( <CookieContext.Provider value={cookieClient}> <Page /> </CookieContext.Provider>, document.getElementById('root'));

and on the server-side:

// index.server.tsximport express from 'express';import { renderToString } from 'react-dom/server';import { Page } from './Page';import { CookieContext } from './CookieContext';import { cookieServer } from './libs/cookie-server';const app = express();app.get('/', (req, res) => { const content = renderToString( <CookieContext.Provider value={cookieServer}> <Page /> </CookieContext.Provider> ); res.send(` <html> <head><script src="./bundle.js"></script></head> <body> <div id="root"> ${content} </div> </body> </html> `);})app.listen(env.PORT ?? 3000);

The concrete implementation of a volatile dependency is composed close to the bootstrap (or main) scripts of the application. This place is named Composition Root.

The benefits of good design of volatile dependencies:

- Loose coupling. The component

Pagedoesn't depend on all possible implementations of the dependency - Free of implementation details and environment. The component doesn't care whether it runs on the client or server-side

- Dependency upon stable abstraction. The component depends only on an abstract interface

Cookie - Easy testing. The component knows only about the interface, you can easily test such a component by injecting dummy implementations using context.

2.3 Be aware of added complexity

The improved design requires more moving parts: a new interface that describes the dependency and a way to inject the dependency.

All these moving parts add complexity. So you should carefully consider whether the benefits of this design outweigh the added complexity.

2.4 Injection mechanisms

While in the the previous example React context was injecting the concerete implementation — React context is only one of the possible options.

The same way you can inject implementations using props:

// Page.tsximport { Cookie } from './Cookie';import { LoginForm } from './LoginForm';interface PageProps { cookie: Cookie;}export function Page({ cookie }: PageProps): JSX.Element { if (cookie.get('loggedIn') === '1') { return <div>You are logged in</div>; } else { return <LoginForm /> }}

However, if the component using volatile dependencies is deep inside the components hierarchy (i.e. is far from Composition Root), you might end up in props drilling. React context, while requiring more setup (context object, useContext() hook), doesn't have this problem.

3. Summary

The components of your Front-end application can use a multitude of libraries.

Some of these libraries, like lodash or even the built-in JavaScript's utilities are stable dependencies and your components

are free to depend directly on them.

However, sometimes the component requires dependencies that may change either during runtime, either depending on the environment, either other reason to change. These dependencies fall in the category of volatile.

Good design makes the components not depend directly upon volatile dependency, but rather depend on a stable interface (by using the Dependency Inversion Principle) that describes the dependency, and then allows a dependency injection mechanism (like React context) to supply the concrete dependency implementation.

What's your opinion: does good design of volatile dependencies worth added complexity?