In Swift self is a special property of an instance that holds the instance itself. Most of the times self appears in an initializer or method of a class, structure or enumeration.

The motto favor clarity over brevity is a valuable strategy to follow. It applies efficiently in most of the cases, and helps to increase the code readability, but... affects code shortness.

Applying this motto to self, the following 2 opposites arise:

- Should you apply the clarity strategy and keep always

selfto access instance propertiesself.property? - Or accessing the property from a method brings sufficient context to omit

selffromself.propertywithout significant readability loss?

The answer is that Swift permits and even encourages you to omit self keyword when it can be done. The challenge is to determine the scenarios when self is obligatory and when optional.

Challenge accepted! Let's dive into an interesting review of self keyword in Swift.

1. Access instance properties and methods

For example the following structure Weather uses self in its initializer and isDayForWalk() method:

struct Weather { let windSpeed: Int // miles per hour let chanceOfRain: Int // percent init(windSpeed: Int, chanceOfRain: Int) { self.windSpeed = windSpeed self.chanceOfRain = chanceOfRain } func isDayForWalk() -> Bool { let comfortableWindSpeed = 5 let acceptableChanceOfRain = 30 return self.windSpeed <= comfortableWindSpeed && self.chanceOfRain <= acceptableChanceOfRain } }// A nice day for a walklet niceWeather = Weather(windSpeed: 4, chanceOfRain: 25)print(niceWeather.isDayForWalk()) // => true

self special property inside init(windSpeed:chanceOfRain:) and isDayForWalk() is the current instance of Weather structure. It allows to set and access the structure properties self.windSpeed and self.chanceOfRain.

The structure looks nice.

Nevertheless accessing every time self property may be excessive. The structure initializer and method provide enough context: everything happens inside the structure. Is it possible to get rid of self?

As mentioned in the introduction, Swift encourages you to omit the self keyword whenever possible.

In the previous example, it is recommended to remove self from isDayForWalk() method. This makes the method shorter:

struct Weather { /* ... */ func isDayForWalk() -> Bool { let comfortableWindSpeed = 5 let acceptableChanceOfRain = 30 return windSpeed <= comfortableWindSpeed && chanceOfRain <= acceptableChanceOfRain }}

Because isDayForWalk() method is always invoked in the context of Weather's instance, Swift enables access of windSpeed and chanceOfRain without self.

Inside the initializer init(windSpeed:chanceOfRain:) the parameters and structure properties have the same names windSpeed and chanceOfRain. Contrary to previous case, now you cannot remove self keyword, because it would create an ambiguity between the parameter and property names.

self helps making an explicit distinction between parameters (windSpeed and chanceOfRain used without self) and structure properties (self.windSpeed and self.chanceOfRain, accessed with self).

Let's make an experiment and still remove self from the initializer:

struct Weather { /* ... */ init(windSpeed: Int, chanceOfRain: Int) { windSpeed = windSpeed chanceOfRain = chanceOfRain } /* ... */}

Looking at the assignment windSpeed = windSpeed, how Swift can understand which variable is a parameter and which is a property? It's an ambiguity, so Swift plainly decides that you mean only the parameters.

As result an error is thrown: cannot assign to value: 'windSpeed' is a 'let' constant. It happens because let constant is assigned to itself windSpeed = windSpeed, which is not allowed.

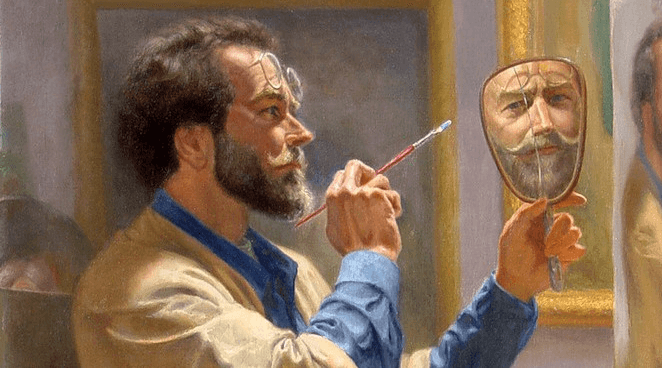

2. To be, or not to be

There were plenty of discussions about the obligatory usage of self to access properties, or contrary to skip self.

The obligatory usage of self brings the benefits of consistency and favors clarity over brevity. You can clearly see the difference between the instance properties (that are prefixed with self.) from locally defined variables. Maybe...

In my opinion, when you have troubles to distinguish instance properties from local variables within a method: you have a different, deeper problem.

When a structure or class has an excessive number of properties (so called God object), you're probably breaking the Single responsibility principle.

If a method uses a big number of these properties and declares correspondingly many local variables, then such method does too many things. Using an explicit self to distinguish somehow properties from variables is a temporary workaround for a bad code.

It should not be that way.

Now imagine a well designed structure or class, which has a single responsibility. It contains only strictly necessary properties. A well written method is performing one determined action and as result its code is simple and obvious.

Surely you don't have the problem to distinguish local variables from instance properties in such a method. The usage of self may be even discouraged, since your adding to obvious code redundant explanations.

So design your classes and structures well, and don't let the methods grow to thousands of lines of code. Then you can omit self without difficulties, and your code becomes even more expressive and concise.

3. Access type properties and methods

self refers to a type (rather than to an instance) when used in a type method.

Let's define following Const structure with type properties minLimit, maxLimit and type method getLimitRange():

struct Const { static let minLimit = 0 static let maxLimit = 250 static func getLimitRange() -> ClosedRange<Int> { return self.minLimit...self.maxLimit }}print(Const.getLimitRange()) // => 0...250

Within the type method getLimitRange() the type properties are accessed using self.minLimit and self.maxLimit. In this case self refers to Const type directly.

Interestingly that you can access type properties using two additional forms.

Firstly you can omit self, and Swift cleverly deduces you're accessing type properties:

struct Const { static let minLimit = 0 static let maxLimit = 250 static func getLimitRange() -> ClosedRange<Int> { return minLimit...maxLimit }}print(Const.getLimitRange()) // => 0...250

Secondly you can indicate the type Const explicitly when accessing the properties:

struct Const { static let minLimit = 0 static let maxLimit = 250 static func getLimitRange() -> ClosedRange<Int> { return Const.minLimit...Const.maxLimit }}print(Const.getLimitRange()) // => 0...250

Const.minLimit is my personal preference when accessing type properties. Const serves as a namespace that groups constants.

I find great that Swift allows 3 ways to access static properties. Use the one you like!

4. Access instance properties and methods in a closure

A closure is a block of code that can be referenced, passed around and invoked when necessary. A closure has access to variables from the environment where it was defined, also called the closure scope.

Sometimes you need to define a closure in a method. The closure can access the local method variables. What's more important you have to explicitly write self to access instance properties or methods within the closure.

Let's define a closure inside a method:

class Collection { var numbers: [Int] init(from numbers: [Int]) { self.numbers = numbers } func getAppendClosure() -> (Int) -> Void { return { self.numbers.append($0) } }}var primes = Collection(from: [2, 3, 5])let appendToPrimes = primes.getAppendClosure()appendToPrimes(7)appendToPrimes(11)print(primes.numbers) // => [2, 3, 5, 7, 11]

Collection is a class that holds some prime numbers.

The method getAppendClosure() returns a closure that when invoked appends a new number to the collection. To access numbers property within the closure you have to explicitly use self keyword: { self.numbers.append($0) } .

The explicit use of self in a closure is an intentional design. Because closure captures the scope variables, including self reference, you may create a strong reference cycle between the closure and self. And you should beware of this potential problem.

To create a strong reference cycle, the common scenario is when a property of an instance is a closure that captures the instance itself. Let's see a sample:

class Person { let name: String lazy var sayMyName: () -> String = { return self.name } init(withName name: String) { self.name = name } deinit { print("Person deinitialized") }}var leader: Person? leader = Person(withName: "John Connor")if let leader = leader { print(leader.sayMyName()) }leader = nil

When the variable leader is assigned with nil, normally the instance should be deinitianilazied. You can expect deinit method to be called that prints "Person deinitialized" message. However this does not happen.

The strong reference cycle creates the problem.

The instance holds the closure reference leader.sayMyName and simultaneously the closure captures and holds the instance reference { return self.name }. Under such circumstances the reference cycle cannot be broken and as result both leader instance and the closure cannot be deallocated.

The solution is to define inside the closure a capture list and mark self as an unowned reference. Let's fix the previous example:

class Person { /* ... */ lazy var sayMyName: () -> String = { [unowned self] in return self.name } /* ... */ deinit { print("Person deinitialized") }}var leader: Person? leader = Person(withName: "John Connor")if let leader = leader { print(leader.sayMyName()) }leader = nil// => "Person deinitialized"

Notice that [unowned self] is added in the closure, which marks self as an unowned reference. Now the closure does not keep a strong reference to self instance. The strong reference cycle between instance and closure is no longer created.

Since leader instance is not necessary leader = nil, the memory is deallocated correctly. The deinitializer deinit is called as expected, which prints "Person deinitialized" message to the console.

I recommend to read more about instances lifetime at Unowned or Weak? Lifetime and Performance.

Important. When you access self in a closure, you should always verify whether a strong reference cycle is not created.

4. Individual self usage

Of course there are plenty of situations when you need to return or modify self directly. Let's enumerate the common scenarios.

Method chaining

When working with classes, you might want to implement a method chaining. Such practice is useful to chain multiple method calls on the same instance, without storing the intermediate results.

The following example is implementing a simple Stack data structure. You can push or pop elements in the stack. Let's take a look:

class Stack<Element> { fileprivate var elements = [Element]() @discardableResult func push(_ element: Element) -> Stack { elements.append(element) return self } func pop() -> Element? { return elements.popLast() } func printElements() { print(elements) }}var numbers = Stack<Int>()numbers .push(8) .push(10) .push(2)numbers.printElements() // => [8, 10, 2]

The method push(:) returns the current instance self. This enables the method chaining calls to push multiple elements 8, 10 and 2 at once into the stack.

Notice that @discardableResult attribute for push(:) method suppresses the warning that the result of the last method call in the chain is unused.

Enumeration case

To find what case holds the enumeration within its method, you can easily query self property with a switch statement.

For example, let's get a string message that describes the enumeration cases:

enum Activity { case sleep case code case learn case procrastinate func getOccupation() -> String { switch self { case .sleep: return "Sleeping" case .code: return "Coding" case .learn: return "Reading a book" default: return "Enjoying laziness" } }}let improving = Activity.learnprint(improving.getOccupation()) // => "Reading a book"

The method getOccupation() accesses self to determine the current enumeration case.

New structure instance

In a structure you can dynamically modify the current instance by assigning to self a new value:

struct Movement { var speed: Int mutating func stop() { self = Movement(speed: 0) }}var run = Movement(speed: 20)print(run.speed) // => 20run.stop() print(run.speed) // => 0

In the mutating method stop() the assignment self = Movement(speed: 0) modifies the current instance to a new one.

5. Conclusion

self is a property on the instance that refers to itself. It's used to access class, structure and enumeration instance within methods.

When self is accessed in a type method (static func or class func), it refers to the actual type (rather than an instance).

Swift allows to omit self when you want to access instances properties. My advice is to rely on shortness and skip self whenever possible.

When a method parameter have the same name as instance property, you have to explicitly use self.myVariable = myVariable to make a distinction.

Notice that method parameters have a priority over instance properties.

Do you think self should be omitted or kept? Feel free to write your opinion in the comments section below!