The plain JavaScript object { key: 'value' } holds structured data. Mostly it does this job well enough.

But the plain object has a limitation: its keys have to be strings (or rarely used symbols). What happens if you use numbers as keys? Let's try an example:

const names = { 1: 'One', 2: 'Two',};Object.keys(names); // => ['1', '2']

The numbers 1 and 2 are keys in names object. Later, when the object's keys are accessed, it turns out the numbers were converted to strings.

Implicit conversion of keys is tricky because you lose the consistency of the types.

A lot of plain object's issues (keys to string conversion, impossibility to use objects like keys, etc) are solved by Map object. This post describes the use cases when it's better to use maps instead of plain objects.

1. The map accepts any key type

As presented above, if the object's key is not a string or symbol, JavaScript implicitly transforms it into a string.

Contrary, the map accepts keys of any type: strings, numbers, boolean, symbols. Moreover, the map preserves the key type. That's the map's main benefit.

For example, if you use a number as a key inside a map, it will remain a number:

const numbersMap = new Map();numbersMap.set(1, 'one');numbersMap.set(2, 'two');[...numbersMap.keys()]; // => [1, 2]

1 and 2 are keys in numbersMap. The type of the keys remains the same.

You can also use booleans as keys inside a map:

const booleansMap = new Map();booleansMap.set(true, "Yep");booleansMap.set(false, "Nope");[...booleansMap.keys()]; // => [true, false]

booleansMap uses booleans true and false as keys.

Inside a plain object, the use of booleans as keys is impossible. These keys would be transformed into strings: 'true' or 'false'.

Can you use further an entire object as a key? Yes, you can. Just be aware of memory leaks.

1.1 Object as key

Let's say you need to store some object-related data, without attaching this data on the object itself.

Doing so using plain objects is not possible. But there's a workaround: an array of object-value tuples.

const foo = { name: 'foo' };const bar = { name: 'bar' };const kindOfMap = [ [foo, 'Foo related data'], [bar, 'Bar related data'],];

kindOfMap is an array holding pairs of an object and associated value.

The downside of this approach is the O(n) complexity of accessing the value by key. You have to loop through the entire array to get the desired value:

function getByKey(kindOfMap, key) { for (const [k, v] of kindOfMap) { if (key === k) { return v; } } return undefined;}getByKey(kindOfMap, foo); // => 'Foo related data'

WeakMap (a specialized version of Map) is a better solution:

WeakMapaccepts objects as keys- Allows straightforward access of value by the key, with O(1) complexity

The above code refactored to use WeakMap becomes trivial:

const foo = { name: 'foo' };const bar = { name: 'bar' };const mapOfObjects = new WeakMap();mapOfObjects.set(foo, 'Foo related data');mapOfObjects.set(bar, 'Bar related data');mapOfObjects.get(foo); // => 'Foo related data'

The main difference between Map and WeakMap is the latter allowing garbage collection of keys (which are objects). This prevents memory leaks.

WeakMap, contrary to Map, accepts only objects as keys and has a reduced set of methods.

2. The map has no restriction over keys names

Any JavaScript object inherits properties from its prototype object. The same happens to plain objects.

The accidentally overwritten property inherited from the prototype is dangerous. Let's study such a dangerous situation.

First, let's ovewrite the toString() property in an object actor:

const actor = { name: 'Harrison Ford', toString: 'Actor: Harrison Ford'};

Then, let's define a function isPlainObject() that determines if the supplied argument is a plain object. This function uses the method toString():

function isPlainObject(value) { return value.toString() === '[object Object]';}

Finally, lets' call isPlainObject(actor). Here's the problem: because toString property inside actor is a string (instead of an expected function), this call generates an error:

// Does not work!isPlainObject(actor); // TypeError: value.toString is not a function

When the application input is used to create the keys names, you have to use a map instead of a plain object to avoid the problem described above.

The map doesn't have any restrictions on the keys names. You can use keys names like toString, constructor, etc. without consequences:

function isMap(value) { return value.toString() === '[object Map]';}const actorMap = new Map();actorMap.set('name', 'Harrison Ford');actorMap.set('toString', 'Actor: Harrison Ford');// Works!isMap(actorMap); // => true

Regardless of actorMap having a property named toString, the method toString() works correctly.

2.1 Real world example

When the user input creates keys on objects? Let's analyze a case.

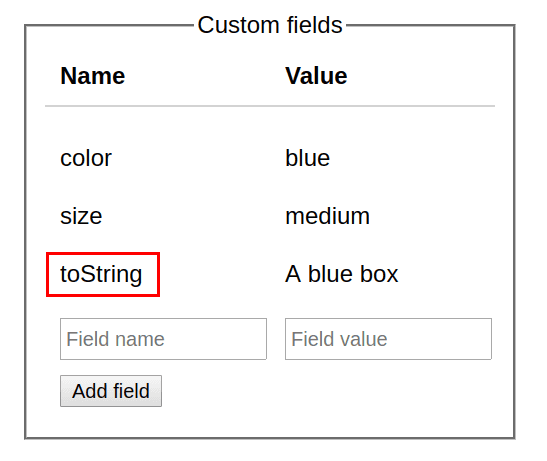

Imagine a User Interface that manages custom fields. The user can add a custom field by specifying its name and value:

It would be convenient to store the state of the custom fields into a plain object:

const userCustomFields = { 'color': 'blue', 'size': 'medium', 'toString': 'A blue box'};

But the user can choose a custom field name like toString (as in the example), constructor, etc. As presented above, such keys names on the state object could potentially break the code that later uses this object.

Don't take user input to create keys on your plain objects!

Because the map has no restrictions over the keys names, the right solution is to bind the user interface state to a map.

const userCustomFieldsMap = new Map([ ['color', 'blue'], ['size', 'medium'], ['toString', 'A blue box']]);

There is no way to break the map, even using keys as toString, constructor, etc.

3. The map is iterable

To iterate plain object's properties are necessary static functions like Object.keys() or Object.entries() (available in ES2017) .

For example, let's iterate over the keys and values of colorsHex object:

const colorsHex = { 'white': '#FFFFFF', 'black': '#000000'};for (const [color, hex] of Object.entries(colorsHex)) { console.log(color, hex);}// 'white' '#FFFFFF'// 'black' '#000000'

Object.entries(colorsHex) returns an array of key-value pairs extracted from the object.

Access of keys-values of a map is more comfortable because the map is iterable. Anywhere an iterable is accepted, like for() loop or spread operator, use the map directly.

colorsHexMap keys-values are iterated directly by for() loop:

const colorsHexMap = new Map();colorsHexMap.set('white', '#FFFFFF');colorsHexMap.set('black', '#000000');for (const [color, hex] of colorsHexMap) { console.log(color, hex);}// 'white' '#FFFFFF'// 'black' '#000000'

colorsHexMap is iterable. You can use it anywhere an iterable is accepted: for() loops, spread operator [...map].

Moreover, map.keys() returns an iterator over keys and map.values() over values.

4. Map's size

You cannot easily determine the number of properties in a plain object.

One workaround is to use a helper function like Object.keys():

const exams = { 'John Smith': '10 points', 'Jane Doe': '8 points',};Object.keys(exams).length; // => 2

Object.keys(exams) returns an array with keys of exams. The size of exams is the number of keys this array contains.

The map provides a better alternative. The property map.size indicates the number of keys-values.

Let's see how to use size on examsMap:

const examsMap = new Map([ ['John Smith', '10 points'], ['Jane Doe', '8 points'],]); examsMap.size; // => 2

It's simple to determine the size of the map: examsMap.size.

5. Conclusion

Plain JavaScript objects do the job of holding structured data. But they have some limitations:

- Only strings or symbols can be used as keys

- Own object properties might collide with property keys inherited from the prototype (e.g.

toString,constructor, etc). - Objects cannot be used as keys

These limitations are solved by maps. Moreover, maps provide benefits like being iterators and allowing easy size look-up.

Anyways, don't consider maps as a replacement of plain objects, but rather a complement.

Do you know other benefits of maps over plain objects? Please write a comment below!