Using ES2015 modules you can chunk the application code into reusable, encapsulated, one-task focused modules.

That's all good, but how do you structure modules? How many functions, classes a module should have?

This post presents 4 best practices on how to organize better your JavaScript modules.

1. Prefer named exports

When I started using JavaScript modules, I had used the default syntax to export the single piece that my module defines, either a class or a function.

For example, here's a module greeter that exports the class Greeter as a default :

// greeter.jsexport default class Greeter { constructor(name) { this.name = name; } greet() { return `Hello, ${this.name}!`; }}

In time I had noticed the difficulty in refactoring the classes (or functions) that were default exported. When the original class was being renamed, the class name inside the consumer module didn't change.

Worse, the editor didn't provide autocomplete suggestions of the class name being imported.

I had concluded that the default export doesn't give visible benefits. Then I switched to named exports.

Let's make Greeter a named export, and see the benefits:

// greeter.jsexport class Greeter { constructor(name) { this.name = name; } greet() { return `Hello, ${this.name}!`; }}

With the usage of named exports, the editor does better renaming: every time you change the original class name, all consumer modules also change the class name.

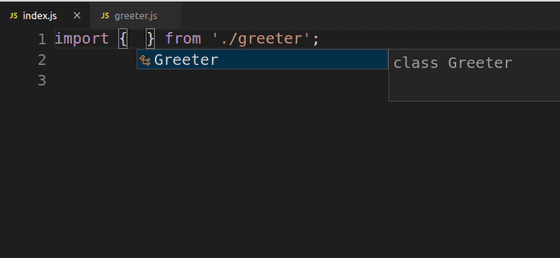

The autocomplete also suggests the imported class:

So, here's my advice:

Favor named module exports to benefit from renaming refactoring and code autocomplete.

Note: when using 3rd party modules like React, Lodash, default import is ok. The default import name is a constant that doesn't change: React, _.

2. No work during import

The module-level scope defines functions, classes, light objects, and variables. The module can export some of these components. That's all.

// Module-level scopeexport function myFunction() { // myFunction Scope}

The module-level scope shouldn't do heavy computation like parsing JSON, making HTTP requests, reading local storage, etc.

For example, the following module configuration parses the configuration from the global variable bigJsonString:

// configuration.jsexport const configuration = { // Bad data: JSON.parse(bigJsonString)};

That's a problem. Because the parsing of bigJsonString is performed at the module-level scope, a heavy operation is executed when configuration module is imported:

// Bad: parsing happens when the module is importedimport { configuration } from 'configuration';export function AboutUs() { return <p>{configuration.data.siteName}</p>;}

At a higher level, the module-level scope's role is to define the module components, import dependencies, and export public components: dependencies resolution process. Separate it from the runtime: parsing JSON, making requests, handling events.

Let's refactor the configuration module to perform lazy parsing:

// configuration.jslet parsedData = null;export const configuration = { // Good get data() { if (parsedData === null) { parsedData = JSON.parse(bigJsonString); } return parsedData; }};

Because data property is defined as a getter, the bigJsonString is parsed only when the consumer accesses configuration.data.

// Good: JSON parsing doesn't happen when the module is importedimport { configuration } from 'configuration';export function AboutUs() { // JSON parsing happens now return <p>{configuration.data.companyDescription}</p>;}

The consumer knows better when to perform a heavy operation. The consumer might decide to perform the operation when the browser is idle. Or the consumer might import the module, but for some reason never use it.

This opens the opportunity for deeper performance optimizations: decreasing time to interactive, minimize main thread work.

When imported, the module shouldn't execute any heavy work. Rather, the consumer should decide when to perform runtime operations.

3. Favor high cohesion modules

Cohesion describes the degree to which the components inside a module belong together.

The functions, classes or variables of a high cohesion module are closely related. They are focused on a single task.

The module formatDate is high cohesive because its functions are closely related and focus on date formatting:

// formatDate.jsconst MONTHS = [ 'January', 'February', 'March','April', 'May', 'June', 'July', 'August', 'September', 'October', 'November', 'December'];function ensureDateInstance(date) { if (typeof date === 'string') { return new Date(date); } return date;}export function formatDate(date) { date = ensureDateInstance(date); const monthName = MONTHS[date.getMonth())]; return `${monthName} ${date.getDate()}, ${date.getFullYear()}`;}

formatDate(), ensureDateInstance() and MONTHS are closely-related to each other.

Deleting either MONTHS or ensureDateInstance() would break formatDate(): that's the sign of high cohesion.

3.1 The problem of low cohesion modules

On the other side, there are low cohesion modules. Those that contain components that are unrelated to each other.

The following utils module has 3 functions that perform different tasks:

// utils.jsimport cookies from 'cookies';export function getRandomInRange(start, end) { return start + Math.floor((end - start) * Math.random());}export function pluralize(itemName, count) { return count > 1 ? `${itemName}s` : itemName;}export function cookieExists(cookieName) { const cookiesObject = cookie.parse(document.cookie); return cookieName in cookiesObject;}

getRandomInRange(), pluralize() and cookieExists() perform different tasks: generate a random number, format a string and check the existence of a cookie. Deleting any of these functions doesn't affect the functionality of the remaining ones: that's the sign of low cohesion.

Because the low cohesion module focuses on multiple mostly unrelated tasks, it's difficult to reason about such a module.

Plus, the low cohesion module forces the consumer to depend on modules that it doesn't always need, which creates unneeded transitive dependencies.

For example, the component ShoppingCartCount imports pluralize() function from utils module:

// ShoppingCartCount.jsximport { pluralize } from 'utils';export function ShoppingCartCount({ count }) { return ( <div> Shopping cart has {count} {pluralize('product', count)} </div> );}

While ShoppingCartCount module uses only the pluralize() function out of the utils module, it has a transitive dependency on the cookies module (which is imported inside utils).

The good solution is to split the low cohesion module utils into several high cohesive ones: utils/random, utils/stringFormat and utils/cookies.

Now, if ShoppingCart module imports utils/stringFormat, it wouldn't have a transitive dependency on cookies:

// ShoppingCartCount.jsximport { pluralize } from 'utils/stringFormat';export function ShoppingCartCount({ count }) { // ...}

The best examples of high cohesion modules are Node built-in modules, like fs, path, assert.

Favor high cohesion modules whose functions, classes, variables are closely related and perform a common task. Refactor big low cohesion modules by splitting them into multiple high cohesion ones.

4. Avoid long relative paths

I find difficult to understand the path of a module that contains one, or even more parent folders:

import { compareDates } from '../../date/compare';import { formatDate } from '../../date/format';// Use compareDates and formatDate

While having one parent selector ../ is usually not a problem, having 2 or more is generally difficult to grasp.

That's why I'd recommend to avoid the parent folders in favor of absolute paths:

import { compareDates } from 'utils/date/compare';import { formatDate } from 'utils/date/format';// Use compareDates and formatDate

While the absolute paths are sometimes longer to write, using them makes it clear the location of the imported module.

To mitigate the long absolute paths, you can introduce new root directories. This is possible using babel-plugin-module-resolver, for example.

Use absolute paths instead of the long relative paths.

5. Conclusion

The JavaScript modules are great to split the logic of your application into small, self-contained chunks.

By using named exports instead of default exports, you could benefit from easier renaming refactoring and editor autocomplete assistance when importing the named component.

The sole purpose of import { myFunc } from 'myModule' is to import myFunc component, and nothing more. The module-level scope of myModule should only define classes, functions, or variables with light content.

How many functions or classes a component should have, and how do these components should relate to each one? Favor modules of high cohesion: its components should be closely related and perform a common task.

Long relative paths containing many parent folders ../ are difficult to understand. Refactor them to absolute paths.

What JavaScript modules best practices do you use?